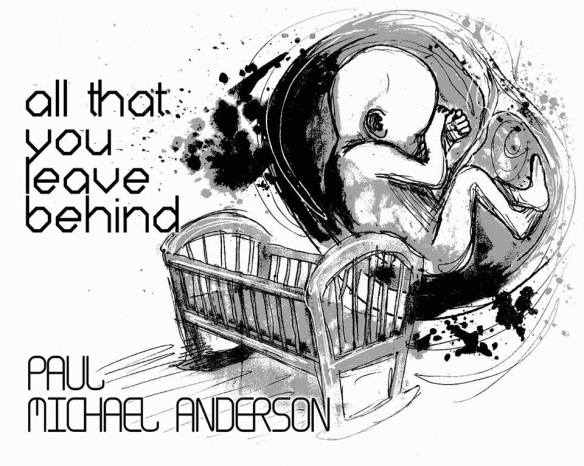

So, this dropped this week:

Jacket image by Matthew Revert

You can pick up the anthology here, as well as read Max Booth III’s origins for the anthology here.

The names are impressive and I was given a quick peek inside the full book before it dropped and, hoo boy, it’s stunning.

But, fuck that, this is about me, right? Right.

(Although, honestly, the other stories are pretty goddamned brilliant. Anyway.)

Story illustration by Luke Spooner

For this, I’m going to dip into the story notes for “All That You Leave Behind”, lifted–but modified–from the deluxe hardcover edition of my upcoming collection Bones Are Made to be Broken:

…So.

Here’s “All That You Leave Behind”.

…I can never describe the depth of the emotions that go through you in the middle of a pregnancy–although, if parents are reading this, you probably know. It’s the world’s worst, most abstract waiting room, when you’re stuck anticipating the moment the doctor comes in with the results of the biopsy report. Even if every checkup and ultrasound come back clean, you still worry. You still fear, but the articulation of that fear is nearly impossible to get across in any way that feels true to you. The truest things in life are the hardest things to express.

There’s nothing more terrifying than parenting. Nothing. The constant realizing—and, thus, terror—that you are responsible for another life, a life that had no say in its creation and existence, a life that looks to you to navigate the ship, can freeze you in your tracks.

But what if you’d geared yourself up for dealing with that fear and realization, only to have it taken away from you?

I was reading Lauren Beukes’s stellar Broken Monsters and there’s a throwaway line in it about a ghost heartbeat. When I heard about Max and Lori’s upcoming anthology and its general theme of white noise, that line recurred to me, and the structure of the story was born. It was fueled by the fears every expecting parent has when they walk in for the monthly check-up or ultrasound. I asked myself the terrible what-if: What if my daughter had been a miscarriage? What if my wife and I had to come to terms with that?

And I wrote my answer to those questions. It…it wasn’t easy. At one point in the first draft, I pulled the little DVD the ultrasound tech gave us, and watched my daughter in utero over and over and over again, and I burst into tears. Just a small clip, under a minute long, but I sat at my kitchen table, my usual writing place, bawling my eyes out late at night with my daughter–completely fine and five years old and asleep with her ragged Bear-Bear–right above my head.

Parenting is terrifying and the fears–even the stupid, irrational fears–never, ever leave you.

In the end, I made it a half-assed homage to Jack Finney, much in the same way that Joe Hill’s “The Black Phone” in 20th Century Ghosts. Note the characters’ surnames. Also, the story takes place in Galesburg, Illinois, a setting that creeps up with Finney (and Hill’s story). Mostly, though, it’s tone. Every writer can be fairly panting—the unfortunate side-effect of wanting to make sure we’re touching the reader—but Finney was the best; he set you up, you knocked you down, but he never had to lead you by the nose.

Finney was pretty neat that way. For me, it was a way to separate myself when the going got tough between my would-be mother and father.

A final note on this story: My wife has not read it. She’s my go-to for draft readings—she once read something like eight drafts of a story—but she couldn’t, she said, because of the subject matter. I understood, of course, even if the writing of the story wound up being cathartic for me, a place to shove all the negative worst-case scenarios that, even five years after my daughter was born healthy and alive, still rested in the back of my head (and, if I’m being fully honest, still do). Because of timing with the deadline–the story, uh, ran a bit long–I went to only one other beta-reader.

She got back to me rather quickly, calling me a bastard and saying I’d made her cry in a Starbucks while she read it. That’s the plan, man. Horror is supposed to make you fearful, terrify you, but first it has to make you feel. You have to empathize. Done to the hilt, you get the tears—or the laughter—as well as the screams.

In the early reviews, the story kept getting mentioned in a positive way. Christine Morgan, for example, called it “beautiful tragic emotional agony”. I’m proud of the story, which shouldn’t be all that surprising, and happy that Max and Lori bought it (and, further, cool with the idea of me reprinting it in Bones; they get some big love in my acknowledgements).

I hope you like it, too. Hell, I hope I make you cry in a Starbucks (sorry, Erinn).